Acupuncture

Acupuncture is the oldest continuously practiced medical system in the world and is used by one third of the world’s population as the primary health care system. Because of its noninvasive nature, safety, and effectiveness for a wide variety of health issues, acupuncture is an increasingly popular modality of alternative and complementary health care in the United States.

How Does Acupuncture Work?

A. Traditional/Eastern Explanation

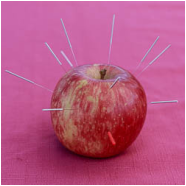

A fundamental principle in acupuncture is the balanced movement of “life force” energy or “vital energy” traditionally called “qi” (pronounced “chee”) within the human body. Qi flows through the body via the channels called meridians. Health is maintained when the qi is full and moving properly. Illness may occur when the qi movement is disharmonious or blocked. Acupuncture treatment involves insertion and manipulation of sterile hair-thin stainless steel needles at specific points along the body’s meridian pathways to restore the natural harmony of qi movement. Such an approach to treatment not only addresses the symptoms but also works with the underlying root causes of disease helping the body heal itself.

Acupuncture is also based on other principles:

B. Western Scientific Explanation

A growing corpus of research-based evidence is being accumulated in the West, which aims to find the anatomic and physiologic bases for acupuncture effectiveness.

Currently, a single overarching and unifying Western scientific theory that would comprehensively explain all of the anatomic and physiological mechanisms underlying the observable therapeutic effects of acupuncture on the body has not been formulated. Several theories are presented throughout the scientific literature.

Current Primary Theories on the Mechanisms of Acupuncture

i. Neurotransmitter Release Theory

A vast body of scientific research suggests that acupuncture stimulates nerve fibers in the muscle which send impulses to the spinal cord that activate three neural centers - spinal cord, midbrain, and hypothalamus/pituitary - to release transmitter chemicals such as endorphins and monoamines which block “pain” messages [1].

ii. Opioids and Opioid Receptors Activation Theory

A large number of studies have been carried out to demonstrate that acupuncture inhibits pain via activation of several types of endogenous opioids, which desensitize peripheral nociceptors and depress the neural activities centrally [2,3].

In a 2009 study at the University of Michigan [3], researchers showed direct evidence of short- and long-term effects of acupuncture therapy on μ-opioid receptors (MORs) in chronic pain patients. Acupuncture therapy evoked both short-term and long-term increases in MOR binding potential in a number of brain regions classically implicated in the regulation of pain and stress in humans, including the cingulated (dorsal and subgenual) regions, insula, caudate, thalamus, and amygdala.

iii. Brain Activity Modulation Theory

Over the past decade, fMRI studies of healthy subjects have shown that acupuncture stimulation evokes deactivation of a limbic-paralimbic-neocortical network, which includes the limbic system. Two major limbic structures, the amygdala and hypothalamus, showed decreased activation during acupuncture stimulation but not during tactile stimulation, which suggests a specific role for these structures in acupuncture action. These limbic structures are central to the regulation and control of emotion, cognition, bio-behavior, endocrine and autonomic nervous functions, and are activated by stress, pain and emotions of negative valence [4].

iv. Adenosine Neuromodulator Release Theory

In a 2010 study at the University of Rochester, researchers have found that insertion and manual rotation of acupuncture needles triggered a general increase in the extracellular concentration of purines, including the adenosine. Adenosine is a neuromodulator with anti-nociceptive properties, so it can act as a local analgesic, thus providing a possible cellular and physiological mechanism to explain the pain relief experienced by acupuncture patients [5].

v. Connective Tissue Stimulation/Vascular-Interstitial Theory

Dr. Helen Langevin, Director of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Professor of Neurological Sciences at the University of Vermont, has been conducting some exciting research for over a decade that shows what actually happens in tissues when an acupuncture needle is inserted and manipulated.

A physiological reaction to acupuncture at the site of insertion called needle grasp has been observed. Dr. Langevin and her colleagues quantified needle grasp’s biomechanical component by measuring the force necessary to pull an acupuncture needle out of the skin and provided evidence of subcutaneous connective tissue involvement in needle grasp [6]. Additionally, her studies have shown an 80% correspondence between the sites of acupuncture points in the arm and the location of intermuscular or intramuscular connective tissue planes [7]. Because loose connective tissue surrounds all nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics, mechanical stimulation of connective tissue generated by needle manipulation could transmit a mechanical signal to sensory nerves and intrinsic sensory afferents directly innervating connective tissue. Further study has shown that acupuncture needle manipulation does not just pull the connective tissue but causes dynamic cellular responses in the connective tissue. Specifically, needle manipulation transmits a signal to fibroblasts, the cells that make up connective tissue, causing them to spread and flatten [8].

The layer of skin into which acupuncture needles are inserted is called the interstitium. New research published in March 2018 in Scientific Reports offered a significant contribution to our understanding of the interstitium, and therefore sheds new light on the Vascular-Interstitial Theory [9].

Previous research on the interstitium suggested it was a layer of densely packed connective tissue lining the digestive tract, lungs, urinary systems and surrounding veins and fascia between the muscles. New and increasingly powerful microscopes now allow scientists to look inside the interstitium - rather than a web of densely packed connective tissue, they found the space is a network of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments. This finding may help to explain why placing acupuncture needles at specific points on the body creates healing elsewhere in the body.

In an article for The Cut, reporter Katie Heaney interviewed one of the authors of this new research, Neil Theise, a clinician and professor of pathology at NYU Langone Health and a proponent of alternative medicine [10]. While the research paper itself did not discuss acupuncture, Heaney asked Theise to weigh in on the possible connections. Theise posited it was possible the research had implications for understanding acupuncture.

“There’s fluid in there [interstitium],” Theise explained Heaney. “When you put the needle [into an acupuncture point], maybe the collagen bundles are arranged into a channel through which fluid can flow.”

The new research shows the interstitium is a structured and organized system in the body. It may be that stimulating acupoints allows interstitial fluid to travel throughout the body, explaining why acupuncture has far-reaching effects, not just offering pain relief at the site where the needles are inserted. Channels of interstitial fluid may be responsible for facilitating the transfer of blood, organic matter and electricity between healthy and injured parts of the body.

References:

Acupuncture is the oldest continuously practiced medical system in the world and is used by one third of the world’s population as the primary health care system. Because of its noninvasive nature, safety, and effectiveness for a wide variety of health issues, acupuncture is an increasingly popular modality of alternative and complementary health care in the United States.

How Does Acupuncture Work?

A. Traditional/Eastern Explanation

A fundamental principle in acupuncture is the balanced movement of “life force” energy or “vital energy” traditionally called “qi” (pronounced “chee”) within the human body. Qi flows through the body via the channels called meridians. Health is maintained when the qi is full and moving properly. Illness may occur when the qi movement is disharmonious or blocked. Acupuncture treatment involves insertion and manipulation of sterile hair-thin stainless steel needles at specific points along the body’s meridian pathways to restore the natural harmony of qi movement. Such an approach to treatment not only addresses the symptoms but also works with the underlying root causes of disease helping the body heal itself.

Acupuncture is also based on other principles:

- The human body is a miniature version of the larger, surrounding universe. Both should be in a state of constructive interaction and harmony with each other for maintaining health

- Harmony between two opposing though complementary forces, called yin and yang, supports health. Disease results from an imbalance between yin and yang

- Five elements (fire, earth, metal, water, and wood) symbolically explain the functioning of the body and how it changes during disease

B. Western Scientific Explanation

A growing corpus of research-based evidence is being accumulated in the West, which aims to find the anatomic and physiologic bases for acupuncture effectiveness.

Currently, a single overarching and unifying Western scientific theory that would comprehensively explain all of the anatomic and physiological mechanisms underlying the observable therapeutic effects of acupuncture on the body has not been formulated. Several theories are presented throughout the scientific literature.

Current Primary Theories on the Mechanisms of Acupuncture

i. Neurotransmitter Release Theory

A vast body of scientific research suggests that acupuncture stimulates nerve fibers in the muscle which send impulses to the spinal cord that activate three neural centers - spinal cord, midbrain, and hypothalamus/pituitary - to release transmitter chemicals such as endorphins and monoamines which block “pain” messages [1].

ii. Opioids and Opioid Receptors Activation Theory

A large number of studies have been carried out to demonstrate that acupuncture inhibits pain via activation of several types of endogenous opioids, which desensitize peripheral nociceptors and depress the neural activities centrally [2,3].

In a 2009 study at the University of Michigan [3], researchers showed direct evidence of short- and long-term effects of acupuncture therapy on μ-opioid receptors (MORs) in chronic pain patients. Acupuncture therapy evoked both short-term and long-term increases in MOR binding potential in a number of brain regions classically implicated in the regulation of pain and stress in humans, including the cingulated (dorsal and subgenual) regions, insula, caudate, thalamus, and amygdala.

iii. Brain Activity Modulation Theory

Over the past decade, fMRI studies of healthy subjects have shown that acupuncture stimulation evokes deactivation of a limbic-paralimbic-neocortical network, which includes the limbic system. Two major limbic structures, the amygdala and hypothalamus, showed decreased activation during acupuncture stimulation but not during tactile stimulation, which suggests a specific role for these structures in acupuncture action. These limbic structures are central to the regulation and control of emotion, cognition, bio-behavior, endocrine and autonomic nervous functions, and are activated by stress, pain and emotions of negative valence [4].

iv. Adenosine Neuromodulator Release Theory

In a 2010 study at the University of Rochester, researchers have found that insertion and manual rotation of acupuncture needles triggered a general increase in the extracellular concentration of purines, including the adenosine. Adenosine is a neuromodulator with anti-nociceptive properties, so it can act as a local analgesic, thus providing a possible cellular and physiological mechanism to explain the pain relief experienced by acupuncture patients [5].

v. Connective Tissue Stimulation/Vascular-Interstitial Theory

Dr. Helen Langevin, Director of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Professor of Neurological Sciences at the University of Vermont, has been conducting some exciting research for over a decade that shows what actually happens in tissues when an acupuncture needle is inserted and manipulated.

A physiological reaction to acupuncture at the site of insertion called needle grasp has been observed. Dr. Langevin and her colleagues quantified needle grasp’s biomechanical component by measuring the force necessary to pull an acupuncture needle out of the skin and provided evidence of subcutaneous connective tissue involvement in needle grasp [6]. Additionally, her studies have shown an 80% correspondence between the sites of acupuncture points in the arm and the location of intermuscular or intramuscular connective tissue planes [7]. Because loose connective tissue surrounds all nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics, mechanical stimulation of connective tissue generated by needle manipulation could transmit a mechanical signal to sensory nerves and intrinsic sensory afferents directly innervating connective tissue. Further study has shown that acupuncture needle manipulation does not just pull the connective tissue but causes dynamic cellular responses in the connective tissue. Specifically, needle manipulation transmits a signal to fibroblasts, the cells that make up connective tissue, causing them to spread and flatten [8].

The layer of skin into which acupuncture needles are inserted is called the interstitium. New research published in March 2018 in Scientific Reports offered a significant contribution to our understanding of the interstitium, and therefore sheds new light on the Vascular-Interstitial Theory [9].

Previous research on the interstitium suggested it was a layer of densely packed connective tissue lining the digestive tract, lungs, urinary systems and surrounding veins and fascia between the muscles. New and increasingly powerful microscopes now allow scientists to look inside the interstitium - rather than a web of densely packed connective tissue, they found the space is a network of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments. This finding may help to explain why placing acupuncture needles at specific points on the body creates healing elsewhere in the body.

In an article for The Cut, reporter Katie Heaney interviewed one of the authors of this new research, Neil Theise, a clinician and professor of pathology at NYU Langone Health and a proponent of alternative medicine [10]. While the research paper itself did not discuss acupuncture, Heaney asked Theise to weigh in on the possible connections. Theise posited it was possible the research had implications for understanding acupuncture.

“There’s fluid in there [interstitium],” Theise explained Heaney. “When you put the needle [into an acupuncture point], maybe the collagen bundles are arranged into a channel through which fluid can flow.”

The new research shows the interstitium is a structured and organized system in the body. It may be that stimulating acupoints allows interstitial fluid to travel throughout the body, explaining why acupuncture has far-reaching effects, not just offering pain relief at the site where the needles are inserted. Channels of interstitial fluid may be responsible for facilitating the transfer of blood, organic matter and electricity between healthy and injured parts of the body.

References:

- Stux, G. and Hammerschlag, R. (2001) Clinical Acupuncture: Scientific Basis. New York: Springer.

- Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement Online 1997, Nov 3-5; 15(5):1-34.

- Harris R.E., Zubieta J.K., Scott D.J., Napadow V., Gracely R.H., and Clauw D.J., (2009). Traditional Chinese Acupuncture and Placebo (Sham) Acupuncture Are Differentiated by Their Effects on μ-Opioid Receptors (MORs). Neuroimage, 47(3), 1077–1085.

- Hue K.S., Marina O., Liu J., Rosen B.R., and Kwong K.K., (2010). Acupuncture, the Limbic System, and the Anticorrelated Networks of the Brain. Autonomic Neuroscience, 157(0), 81–90.

- Goldman N., Chen M., Fujita T., Xu Q., Peng W., Liu W., Jensen T.K., Pei Y., Wang F., Han X., Chen J.F., Schnermann J., Takano T., Bekar L., Tieu K., and Nedergaard M., (2010). Adenosine A1 receptors mediate local anti-nociceptive effects of acupuncture. Nature Neuroscience, 13(7), 883-888.

- Langevin H.M., Churchill D.L., Wu J., Badger G.J., Yandow J.A., Fox A.R., and Krag M.H., (2002). Evidence of Connective Tissue Involvement in Acupuncture. The FASEB Journal. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0925fje.

- Langevin H.M. and Yandow J.A., (2002). Relationship of Acupuncture Points and Meridians to Connective Tissue Planes. The Anatomical Record (New Anat.), 269, 257–265.

- Langevin H.M., Bouffard N.A., Badger G.J., Churchill D.L., and Howe A.K., (2006). Subcutaneous tissue fibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling induced by acupuncture: evidence for a mechanotrasduction-based mechanism. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 207(3), 767-774.

- Benias P.C., Wells R.G., Sackey-Aboagye B., Klavan H., Reidy J., Buonocore D., Miranda M., Kornacki S., Wayne M., Carr-Locke D.L., and Theise N.D., (2018). Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Scientific Reports 8, 4947. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-23062-6

- https://www.thecut.com/2018/03/do-we-finally-understand-how-acupuncture-works.html